Discover History

History & Culture

The forest was named for Francisco Vasquez de Coronado, who, in 1540, journeyed to the Zuni and Hopi villages through part of what is today the Coronado National Forest.

At least fourteen different shifts in government land were made before the Coronado National Forest, part of which lies in New Mexico, attained the form that it has today.

The first move was the creation of the Santa Rita Forest Reserve on April 11, 1902, followed in July of that year by the Santa Catalina Forest Reserve, Mount Graham Forest Reserve, and the Chiricahua Forest Reserve. On November 5, 1906, the Baboquivari and Peloncillo Forest Reserves were formed, followed the next day by the Huachuca Forest Reserve, and on November 7 by the formation of the Tumacacori Forest Reserve. On May 25, 1907, the Dragoon National Forest was created.

The nine original forest reserves went through their first consolidation in 1908, on the same day. On July 2, the Baboquivari, Huachuca, and Tumacacori National Forests were consolidated into the Garces National Forest. At the same time, the Santa Rita, Santa Catalina, and Dragoon National Forests became the first to bear the name Coronado National Forest. The third consolidation was made when the Chiricahua and Peloncillo National Forests became the Chiricahua National Forest. Mount Graham National Forest merged with parts of the Apache, Tonto, and Pinal National Forests to create the Crook National Forest.

On September 26, 1910, the Galiuro Mountains were added to the Crook National Forest. One of the first additions to the Coronado National Forest occurred on July 1, 1911, when Garces was added to it. Chiricahua National Forest joined the Coronado on June 6, 1917.

The final move took place on October 23, 1953, when 425,674 acres of the Crook National Forest were transferred to the Coronado National Forest from the Santa Teresa, Galiuro, Mount Graham, and Winchester divisions of the Crook National Forest. The Crook National Forest was abolished with the remaining parts of the Crook National Forest being consolidated with the Apache and Tonto National Forests.

Visiting the Coronado National Forest can be a bit like taking a cruise, albeit a landlocked one, among Sky Island mountain ranges that tower more than 5,000 feet above the intervening seas of grass and desert. The members of this earthbound archipelago stand as destinations in an overland voyage for which your car, bicycle, or hiking shoes can serve as a vessel. Catchers of clouds and cool air, the Sky Islands serve as home to a diverse array of plant and animal species, some of which can best be described as having been marooned by the last ice age. As the cloak of forests and woodlands that covered the area during the Pleistocene was pushed back by gradual warming, remnants clung to the highlands. The lower extremities of those ice age remnants form the boundaries of the various Districts of the Coronado National Forest.

The sky islands of southeastern Arizona are characteristic of a basin and range topography that spans the southwest and extends north and west into Oregon. This rugged landscape was formed by a combination of volcanic activity and a consequence of plate tectonics called block faulting. Block faulting is a process in which the earth’s surface is cracked (faulted) into large blocks which then slide up or down in relation to one another as stress continues. The landscape that results is a mosaic of high ground (ranges) and broad flat valleys (basins) such as we see in southeastern Arizona today.

The forces that bent and buckled this region were most active during three dramatic geologic events. Between 75 million and 50 million years ago, as the continent of North America rode up and over the floor of the Pacific Ocean, a combination of explosive volcanism and radical uplifting known as the Laramide Orogeny was unleashed. These earth-shaping (and shaking) events created a mountain range of such magnitude that its rivers deposited silt as far away as present-day Wyoming. After 25 million years of wearing down, two more periods of active volcanism and block faulting shaped the area. The result was, roughly, the landscape we see today.

Even as volcanic cataclysms and grinding uplifts were creating the Sky Islands, erosion was tearing them down. As a result, the basins that separate them have been filling with geologic debris. As you drive across the basin and range topography, keep in mind that a sizable portion of it is beneath you. What seems to be a small hill may be a mountain buried “to its neck.”

Though the mountain ranges of southeastern Arizona can trace their roots back to similar if not common events, each is unique. The Chiricahuas, for instance, contain areas where volcanic outflows pooled in depressions and the ash and dust that settled there fused into a type of rock called “welded tuff.” Nature has weathered this material into a bizarre collection of pinnacles and balanced rocks that compose one of the most striking landscapes in the West. The Dragoons and Santa Catalinas have their eye-catching natural sculptures too, but these rounded boulder scapes are made of granite, a volcanic material that oozed rather than flowed and, in most cases, never broke the surface. In the Huachucas, Santa Ritas, Rincons, and Patagonias, rocks of diverse origins were injected with intrusions of molten magma rich in metals that became the focus of extensive mining activity in historic times. Such mining activity, in varying degrees, was common to all ranges in the area.

During the time that glaciers covered much of North America, southeastern Arizona was cooler and wetter than it is now. Lakes filled the valleys, and turtles and salamanders swam in their waters. Surrounding those lakes were extensive forests and savannas where mastodons, mammoths, llamas, and camels grazed and browsed. These plant eaters, in turn, provided food for predators just as exotic as their prey–jaguars, dire wolves, and short-faced bears.

As the glaciers melted, southeastern Arizona became warmer, and its vegetative communities began to change. The forests retreated to the north, toward the cool, moist conditions that best supported them. But they also endured on the slopes of the mountains, where the air was cooler and the rains more frequent. As the weather continued to warm, Sonoran and Chihuahuan desert vegetation invaded from the south, displacing some of the grasslands from the valleys. In the lowest areas, such as the Tucson basin, the bristly newcomers even began following their predecessors up the mountains.

As a result of this warming and retreating, the plants left over from the ice age were arranged on the mountain slopes in such a way that the species that required the coolest and most moist conditions were perched nearest the summits or clustered in cool canyons on north slopes. Those that required less moisture and could stand more heat were arranged according to temperature and moisture conditions that suited them best, at lower elevations.

C. Hart Merriam was the first to describe this loose stratification of plants and animals in his 1889 biological study of the San Francisco Peaks, the highest mountain in Arizona. He dubbed the various layers “life zones.” Since that study, it has been suggested that the Sky Islands of the Coronado provide an even better example of this principle than the northern Arizona volcano where it was first observed.

The result of all these ecological comings and goings has been to enrich the area with amazing biodiversity. A one-hour drive up one of the Coronado’s taller mountain ranges, traversing the various life zones that cover its slopes, can treat the traveler to changes in plant communities equivalent to a trip from the deserts of Mexico to the forests of Canada. If you’re willing to add a little hiking to the end of that trip, it can take you to the Hudsonian Zone (in the Chiricahuas and Pinaleños), where stands of Engelmann spruce resemble the forests of northern British Columbia.

Though the mastodons of the ice age remain only as fossils, there are plenty of fascinating animals to be found among these diverse habitats. In sheltered canyons, such as Ramsey in the Huachucas, Madera in the Santa Ritas, and the South Fork of Cave Creek in the Chiricahuas, the variety of bird species attracts birdwatchers from around the world. Sycamore Canyon in the Nogales District shares rare plants with isolated sites in Mexico and Asia’s Himalayas. The Pinaleños of the Safford District are a geologic ark that is home to several species that are found nowhere else on Earth. It will surprise some to learn that this mountain surrounded by desert supports one of the densest black bear populations in North America.

The roots of human habitation in southeastern Arizona are still being traced, but the clues that have been uncovered have much to say. Finely shaped stone points of the Clovis Culture, found in conjunction with the remains of ice-age mammoths, tell us that these intrepid hunters ranged here as much as 11,200 years ago. The simple grinding and crushing tools of a people archaeologists call the Cochise Culture indicate that they responded to the disappearance of ice-age mammals by broadening their food supply to include a wide range of plants, as well as the deer and other animals which we see in southeastern Arizona today.

Eventually, pottery-making, and agricultural peoples, such as the Mogollon and Hohokam, appeared. Their cultures reflect increasingly refined adaptations to local environments, and knowledge obtained from people living to the south, in present-day Mexico. Archaeologists debate their relationship to the later Sobaipuri, Tohono O’Odham and Pima.

These latter peoples were the inhabitants of the land of the sky islands when two vastly different groups of newcomers arrived on the scene, at nearly the same time. The Apaches were Athabascan nomads from what we now call Canada. The Spaniards were fresh from their conquest of Mexico.

In 1539, Fray (Friar) Marcos de Niza and a companion named Esteban became the first non-Indians of reliable record to enter what is now Arizona. They came searching for the Seven Cities of Cibola, a metropolis rumored to be richer than the gold-drenched capital of Aztec Mexico. Instead, they found the simple mud homes of Pueblo Indians.

Lured by de Niza’s tales of treasure (though he had found none), Don Francisco Vásquez de Coronado mounted a second expedition one year later. The entry of the Conquistadores into what is now the United States is marked by the Coronado National Memorial at the southern end of the Sierra Vista Ranger District. Evidence indicates that Coronado proceeded along a course roughly duplicated by the Montezuma Pass to Sonoita's scenic drive through the San Rafael Valley. He continued north and east via the San Pedro and Gila River valleys, on a trek that eventually took him and his army to modern-day Kansas. The expedition, however, was considered a total failure. The land through which it passed held so little value to the Spaniards that they went back to Mexico and didn’t return for nearly a century.

In the late 1600’s the lure of another type of reward, souls for the saving, brought Father Eusebio Kino to the Santa Cruz Valley. Kino, along with other Jesuits and Franciscans, built a system of missions across the Southwest where the padres vied for the faith of the native Sabaipuris, Pimas, and Tohono O’odham, as well as the Apaches. On the heels of the missionaries came silver miners armed with tools for extracting from the land that their predecessors had failed to find for the taking among its residents.

Though faced with an aggressive and better-armed society, indigenous peoples kept to their traditions and periodically rose to force the newcomers to withdraw. Most defiant were the Apaches, who roamed the region’s mountains in relatively small bands and proved unconquerable. This clash of cultures sent waves of conflict across the Southwest for nearly 300 years. Some of the most violent of those waves swept the region free of Europeans for a time, but those times were never long.

The end of the Mexican-American War in 1848 changed this scenario drastically. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ceded most of what is today New Mexico and Arizona to the United States, and the direction of expansion shifted abruptly from north-south to east-west. Railroad and stage routes were scouted to provide a route west across the mountains and deserts to California. In 1857, the first stage line to cross Arizona, the Jackass Mail, opened for business.

These routes brought a flood of immigrants from prospectors to storekeepers, as the Apaches fought desperately to stem the tide. Striking from refuges, such as Stronghold Canyon in the Dragoon Mountains and hideouts in the Chiricahua Range, Apache bands were a constant threat to such outposts as Butterfield Stage Stop and Fort Bowie. Efforts to find a peaceful accommodation, by men such as Indian agent Tom Jeffords and the Chiricahua Apache chief Cochise, were swept aside. Isolated homesteads, such as the Hank and Yank Ranch at Sycamore Canyon, became battlegrounds in this fight to the finish. With Geronimo’s surrender in 1886, in Skeleton Canyon of the Peloncillo Mountains, and his deportation to a prison in Florida, all but a few stragglers of the once-feared Chiricahua were removed from their homeland.

Even before the Apache Wars ended, yet another mining rush was sweeping the region. Boomtowns such as Greaterville in the Santa Ritas, Washington Camp and Harshaw in the Patagonias, Reef in the Huachucas, and Ruby in the Oro Blancos became the site of feverish fortune hunting. Swindles and speculation probably produced greater returns than mining, but whatever the source of a miner’s stake it was equally well-received in the gambling halls and bawdy houses of Tombstone and Bisbee.

Such intense activity required an enormous amount of resources. The towns needed building materials, fuel, water, and sustenance. The Indians who now lived on reservations had to be fed, as did the military garrisons that guarded them. The same mountains that supplied ore for the mines provided wood and water for the towns. The grasslands that separated the mountains fattened herds of beef cattle.

Cattle had been brought to the area by Father Kino as early as the mid-1600s. With the beginning of full-scale economic development, livestock grazing in the American Southwest entered its golden age in the late 1800’s. Fortunes were made in beef just as they were in silver, copper, and tungsten. But there were challenging times, too, as droughts, a fickle market, and the depletion of the range through overgrazing knocked many a cattle baron off his high horse.

After the turn of the century, attention turned to southeastern Arizona’s Sky Islands for yet another resource, recreation. As early as the mid-1800s, areas such as Hospital Flat in the Pinaleño Mountains and the town of Oracle in the foothills of the Santa Catalinas were being used as refuges from the heat and malaria of lowland forts. At about the same time that 15 upland areas were designated U. S. Forest Reserves (between 1902 and 1907), residents of burgeoning desert communities began trekking to the mountains to escape the summer heat. Areas such as White House (Madera) Canyon in the Santa Ritas, Columbine in the Pinaleños, and Summerhaven in the Santa Catalinas were among the most popular of these forest retreats.

Roads such as the Swift Trail out of Safford and the Control Road and Catalina Highway from Tucson were built to provide access to the new recreation areas. Campgrounds, picnic areas, and trails were added by the Depression-era Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930’s. Today, the cool forests and magnificent scenery of the Coronado National Forest’s five Ranger Districts continue to attract visitors in numbers that have grown to the point that they threaten to overcrowd some of the very attractions that drew them. The history of this exceptional area is, of course, still unfolding. With such an illustrious and colorful past, it seems assured that its future will be notable as well.

A photo in time...

...leads to exploration...

...a thirst for knowledge...

...and discovery.

Street Smarts: Mercer Spring

From The Arizona Daily Star

Posted January 6, 2019 by David Leighton

In The Foothills II subdivision of the Catalina Foothills, the streets are named for places in the Santa Catalina Mountains, including one, Mercer Spring Place, derived from a now dry spring in Molino Basin.

The spring, in turn, is named for Caddell N. “Dell” Mercer, an early rancher in Molino Basin.

He was born in 1903 in a family home that is now part of the old Blue Front Inn on Main Street in Mammoth. The Mercer family had been in the Arizona Territory since T. Lillie Mercer arrived in Tubac in the 1870s.

Dell’s father, James "Jimmie" Mercer, was later hired by the Pima County Sheriff’s Department as a county ranger to help stop cattle rustling. In this role, in December 1914, he was ambushed by a suspect on a ranch near Pantano, Arizona, and killed. A sign in the area now honors his memory, but lists him as a “deputy sheriff”.

Dell’s mother, Bessie, and Jimmie had divorced in about 1909, and in 1911 she married John (Tewksbury) Rhodes, who adopted Dell and his brothers Virgil and Edgar; the couple later had a son, Tom Rhodes.

The family moved to the old Atchley ranch across the San Pedro River from Mammoth, and then south a few miles to the 111 Ranch, formerly owned by John Schoenholzer, (pronounced Shown-Holzer), namesake of Schoenholzer Canyon in the Galiuro Mountains.

Later they relocated to the foothills of the Galiuros to what they called the Home Ranch, where Dell lived most of his early life. His mother named an odd-shaped rocky hill near the family home Wildcat Hill after hearing a wildcat growling on it.

Rhodes also at one point obtained the nearby YLE Ranch, namesake of YLE Ranch Road and YLE Canyon.

In 1927, Dell, then 24 and living in or near Globe, wed Pearl Swingle. The couple would have three children, Lois, Lloyd and Edgar.

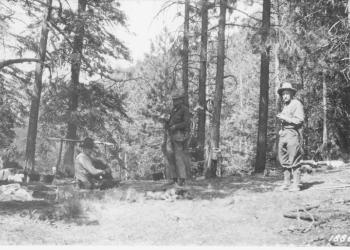

Two years later, Dell obtained some land in the foothills of the Santa Catalina Mountains, with his stepfather John Rhodes staking him 50 to 60 cattle to help start the ranch. Along with his brothers, Edgar Mercer and Tom Rhodes, and a cowboy named Charles Fowler, he drove the cattle from the San Pedro River area to Molino Basin in the Catalinas.

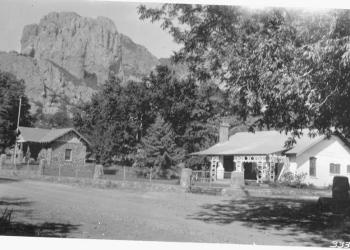

The land at the bottom of the Catalinas, in the foothills, had a ranch house, a tin shed, corrals and loading chutes.

Lois Mercer, years later, wrote about the second ranch at Molino Basin: “There was a camp and corrals up in the mountains where we lived in tents and cooked over a campfire all summer. Dad packed all our supplies up the mountain by pack mule. It was a very rough ranch, mostly rock. I rode on a pillow in front of mom. I would play in the dirt at the camp, and sometimes she would find me asleep in a cow pie or trying to eat juniper berries.”

There was a natural spring near the camp that provided water for the family and whose name would carry on the family’s legacy long after they had left the land.

In October 1933, a temporary prison camp was set up at the bottom of the mountain, about 2 miles east of the Mercer Ranch, to house the prisoners who would build the road up to Summerhaven. Dell was employed as a packer to transport supplies from the prison camp to a temporary road survey camp at Bug Spring.

In 1936, the U.S. Geodetic Survey, a federal agency, was in the midst of an extensive project to survey Arizona and other locations across the U.S. That year, a survey crew traveled north on Bear Canyon Road and then east on Snyder Road, through Jesse and Maude Snyder’s homestead, and past the painted sign that read “Mercer Ranch” to arrive at the family’s house.

At one point during the survey process, the crew climbed for about an hour to the foothill ridge, just west of Soldier Canyon in the Catalinas, and placed a survey benchmark on a knoll, labeling it “Mercer.” The crew also installed a corresponding azimuth mark in the Mercer Ranch yard, at the foot of the ridge. This mark still appears on USGS maps as “Mercer” or “Mercer, 3792” and is sometimes mistaken for a mountain or peak name.

The next year, when crews began to construct the part of the road just above the Mercers’ camp at Molino Basin and to dynamite rock there, the prisoners would call down to warn Pearl. She would grab her children, run as far down the canyon as they could and hide behind trees, so they wouldn’t get hit by flying rocks.

Around 1940, the U.S. Forest Service canceled Dell’s grazing permits, which ended the second ranch in Molino Basin, forcing him to sell off most of his cattle.

Lois would write, “I was twelve when I went out on the last round up. We brought the cattle off the mountain on the road the prisoners built. Now the road to Mount Lemmon goes right through our old horse pasture in the foothills. ... It’s also wall-to-wall houses now, where before there were no houses for twenty miles around.”

Around 1943, Dell and Pearl divorced and within two years he sold the Mercer Ranch at the bottom of the mountain.

He moved back to Mammoth and began farming along the San Pedro River and training race horses, which he raced in Tucson and Phoenix. He met and married much younger Lydia Parra Bufanda; they would have children Kenneth, Thomas, Lydia, Dell Mario and Larry.

Dell sold the Mammoth farm and purchased Rancho Tabiquito near Carbo, Sonora, and leased a smaller nearby ranch, El Ranchito.

During the time at the ranches, mountain lions would often kill Dell’s young horses and cows, resulting in him purchasing hunting dogs and tracking and killing several mountain lions.

His second wife Lydia, now 93 years old, recently recounted, “Dell was also hired by local ranchers, near and far, to rid them of predatory mountain lions. ... The most … famous client was Clark Gable, which he took on a mountain lion hunt. Mr. Gable’s commitments in Hollywood cut his trip short and they were not able to get their prey. Dell would comment that Clark was very athletic and a likable fellow.” This event is recounted in the book “ONZA! The Hunt for a Legendary Cat” by Neil B. Carmony.

In the late 1970s, Dell sold Rancho Tabiquito and relocated with the family to California, where he remained until his death in 1997.

Kentucky Camp

Late in the 19th century, the east slope of the Santa Rita Mountains bustled with the activity of hundreds of miners. Gold had been discovered in 1874, in what became known as the Greaterville mining district. It proved to be the largest and richest placer deposit in southern Arizona.

Placer deposits consist of gold mixed with sand and gravel. The miners quickly discovered that water was more precious than gold. In most places, they could wash the sand and gravel with water to separate the gold, but the arroyos of the Santa Rita Mountains were dry. Miners hauled sacks of dirt to the few running streams, or packed water to their claims in canvas and goatskin bags, on the backs of burros. The rich deposits that could repay these efforts were worked out by 1886, and the miners gave up and moved on.

However, in 1902 a California mining engineer named James Stetson thought he could solve the water problem. He conceived a grand scheme to channel seasonal runoff from Santa Rita's streams into a reservoir that would hold enough water to last ten months. With that, he could keep a mine operating.

This sketch of George McAneny was drawn for a San Jose, California newspaper in 1905. A report by the Arizona Territorial Geologist described McAneny as "formerly of Tombstone." Perhaps his experience with that mining boomtown led him to look favorably on another opportunity to invest in an Arizona mine. He was no doubt greatly disappointed by Kentucky Camp, however. Before the project was abandoned, he spent between $125,000 and $175,000 in developing the mine and received only $3,000.

Stetson convinced a wealthy Californian, George McAneny, to invest in the plan, and with other investors from Tucson, they formed the Santa Rita Water and Mining Company to bring it to life. After extensive prospecting in the Greaterville district, Stetson and McAneny decided to begin mining in Boston Gulch. Nearby Kentucky Gulch was selected as the site for the mining headquarters, and from 1902 to 1906, the buildings at Kentucky Camp served as the offices and residences for company employees. The origins of the names "Boston Gulch" and "Kentucky Gulch" are obscure - perhaps they were named for the homes of miners who worked the gulches in the 1870s.

Tragedy struck in 1905. The day before a meeting with stockholders, Stetson died in a fall from a Tucson hotel window. McAneny's finances and health deteriorated, and although the other partners tried to keep the operation going, it was abandoned by 1912. The buildings and land were purchased by an attorney for the McAneny family and were used as a cattle ranch until the 1960s when it was sold to ANAMAX Mining. The Coronado National Forest acquired the site through a 1989 land exchange. To satisfy public interest in the history of mining, the Forest is working with volunteers and other partners to preserve and interpret Kentucky Camp.

The five buildings that remain at Kentucky Camp were built around 1904. The largest was probably used as an office by the Santa Rita Water and Mining Company. Later, it became the main ranch house. A small building behind the office was used to process gold samples, as evidenced by liners that came from an assay furnace. A large barn lies in ruins opposite a small house where Stetson may have lived, and another small house lies at the far end of the site.

- The largest building, sometimes called the "hotel," was probably the office of the Santa Rita Water and Mining Company and provided temporary accommodation for visitors or employees.

- The interior of the gold processing building. Washing of samples may have occurred in the basin on the right; retorting of amalgam on the bench to the left.

- The barn was in ruins before the stabilization of the walls. The collapsed roof has since been removed, and the walls braced.

- There are two adobe cabins at Kentucky Camp.